In the first published results from a clinical trial using human embryonic stem cells, two legally blind patients who received an injection of hESC-derived cells in one eye have experienced no harmful side effects and appear to have slightly better vision. Although the result is preliminary, it is an important milestone for the struggling hESC field.

In the first published results from a clinical trial using human embryonic stem cells, two legally blind patients who received an injection of hESC-derived cells in one eye have experienced no harmful side effects and appear to have slightly better vision. Although the result is preliminary, it is an important milestone for the struggling hESC field.

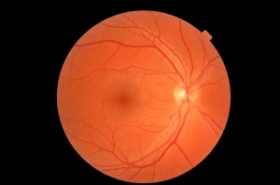

Since their discovery 13 years ago, hESCs have shown great promise for treating diseases, but they have also been dogged by safety issues and ethical concerns because deriving the cells often destroys human embryos. In the only ongoing clinical trials involving hESCs, the biotechnology company Advanced Cell Technology (ACT) of Marlborough, Massachusetts, derived a type of cell called retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which sustains the retina’s light-sensing photoreceptors. Collaborators at the University of California, Los Angeles, then used these cells to treat an elderly woman who has dry age-related macular degeneration and a woman in her 50s who has Stargardt macular dystrophy, a rare inherited disease. The researchers injected 50,000 RPE cells suspended in a solution under the retina in one eye of each patient.

Four months after receiving the treatment, the patients have not developed any tumors or abnormal growths that have sometimes been seen in animals receiving hESC-derived cells, the team reports online today in The Lancet. The patients, who received immune-suppressing drugs for 12 weeks to prevent their bodies from attacking the cells, also have not shown inflammation or other signs of rejecting the cells.

The researchers detected RPE cells in the eye of the patient with Stargardt disease but not in the patient with age-related macular degeneration. However, both women’s vision seemed to improve, particularly in the patient with Stargardt. She went from seeing only hand movements to being able to read a few letters on an eye chart. The authors caution, however, that measuring small visual improvements is difficult and that they can’t say for sure that the changes were not the result of the immune-suppressing drugs or a placebo effect.

“It’s a long time coming. It’s rewarding to finally see years and years of research translated to the bedside,” says Robert Lanza, CEO of ACT.

Source : news.sciencemag.org