Roof of Bangladesh is Sajek – a valley surrounded by high hill ranges of evergreen forest along the border of Bangladesh and India at southeast– is one of the unexplored areas as far as the biodiversity is concerned. With the inspiration of Dr. Reza Khan, he who visited the valley earlier, we got tempted to explore the wilderness of the site. Accordingly we formed a team on behalf of a TV documentary entitled “Nature and Life” of Channel i to lead a nature expedition at Sajek Valley.

Prior to starting our expedition, we got completed all formalities in terms of Permission from relevant govt. departments and equipping us with all required logistics. The team was comprised of a team leader, production manager, cameraman, camera assistant, wildlife scout, field assistant, two local guides and a driver. Dr. Reza khan, national award winning wildlife scientist joined us as honorary adviser. We organized all modern audio-visual equipment, GPS, Binocs, Telescopes and safety devices for making the expedition fruitful.

It was winter of 2011 amidst foggy and chilly weather when we cruised to the valley by a four-wheel drive Toyota land cruiser. Our carrier is locally known as “Chander Gari” means a vehicle that is capable to cruise even over rugged moon surface. We boarded the rented vehicle from Baghaihut the place where we left our posh Toyota Hiace micro-bus as because Posh cars are not fit to run on the roads with high ups and downs with countless sharp bends. Some of us took the roof of the jeep to have better view of hills and take shots of the hillscapes and the wildlife passing on our way. The road is spiral and bordered with lash evergreen forest.

Atop a hill we could get a great view of the surroundings as far as the eyes go. All lands around us are undulating hill ranges covered with some forms of greeneries. Although the virgin natural forest is no more but secondary growth with herbs and shrubs are in abundance. Some of the hill sides and slopes are covered with dense bamboo thickets of more than 7 species. The Hill streams are running gradually to the gorges with steeper banks. All these small hill streams joined together and forms rivers like River Kasalong, Mainy , Sangu and Matamuhuriy those who originates and merged to the sea within the territorial boundary of the country. A few mother trees reaching high up in the sky are the symbol of lost forest. These are kept by the forest department as genome refuse. Hill mynas are seen calling in loud whistles while flying from one place to other. They were seen in large groups varying from 5 to 100 in numbers. Possibly this is the place where you may encounter this large flocks, nowhere else. Similarly, you can encounter the Chestnut-headed bee-eater in hundreds either perching on denuded hill edges or congregating on single tree with high-toned chorus.

Although our travel in winter season, but we got thirsty because of our hectic hill climbing. We get down in a valley where an old hillstream is running. First of all we drank the stream water by using bamboo pipes. Our local guide instantly made the bamboo drinking pipes by cutting the tender bamboos from the bush. This is the traditional indigenous way of drinking stream water in a safe and at ease way. The water is heavy and sweet enough to meet our thirst. Water is running slowly and looks transparent with bluish reflection. You can see the hill shrimps, mollusks, water bugs and tiny fishes with your naked eyes in the crystal clear water. You will find stones of various sizes and shapes all along the stream. Smaller stones and pebbles are rolling down while the larger and heavier ones are seen stand still. Hill dwelling people revered these huge stones. They used to pray, Lit candles and offer suits and fruits on the boulders. Dr. Khan was looking at the crevices and cracks of the heavy boulders and all on a sudden he shouted to us …. Hi guys! Come here and see something interesting. We all rushed to him and were amazed seeing the tiny and brilliantly colored frogs known as “Assam Cascade frog/Beautiful Stream frog” mimicking the dampen mosses and bryophytes. The frog was so camouflaged with the environment and it is hard to locate if the frog does not move. This tiny frogs croaking very loudly. While walking at knee deep streams, we also saw Ornate Microhylid and Berdmore’s Narrow mouthed frogs. All of them living in the hill streams and hunting the small insects, beetles and crickets.

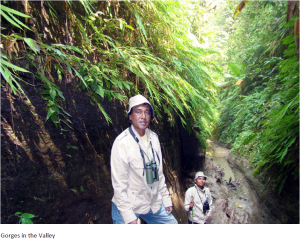

On the wet walls of the stream we saw the shinny skinks where the hanging grasses and lichens are dense. In one bend of the stream the hanging plants, climbers, vines and tree ferns are very dense. We are crawling to cross the cave like entrance; suddenly we noticed a pair of White-crowned forktail- quite beautiful birds. These birds are mostly stream dwelling and prefers dense forested cool and shady places. Their tail is bifurcated and very sharply forked. They are seen dancing on the rocks rolling in running water and feeding on fishes and insects of the hill stream.

We reached the hill top of our dream Sajek valley in the afternoon where the Mizo, Lusai and Tippera villages are located. The Headman Mr Lanthanga Lusai welcomed us with local drinks and homemade cakes. We literally dumped all of our luggages in the compound of headman and rush to the nearby hills as the light is in our favor photograpy.

Just at the doorsteps of the Church at a hill top there exists a huge old Banyan tree. We spotted more than 50 Hill Mynas there. They were feeding on the ripe yellow fruits of the tree hanging upside down position. I have never seen the Hill Mayans in the wild as close as this in my 20 years of nature watch around the world. The area was really lively with the Chorus of Mayans and the surroundings became bright with the brightness of Mayas feather color. There are few other old and tall Bombax trees bearing red flowers on the nearby hills . Birds are moving around these trees and enjoying their meals. We were hypnotized with the rhythmic calls and flights of Maynas over the colorful plants waving around the Sajek valley. Our camera unit was initially puzzled and got frizzed by watching the Maynas whirlpool but later they were able to get some clear and good shots of the flights and feeding behavior of the birds flocks. We all together watched their behavior in the whole evening. Some barbets and parakeets were also seen feeding in association with Mynas. We noted all possible ecological features of the habitat including, vegetation canopy, eco-tones, species assemblage and diversity, etc.

We were very tired and walked hurriedly to our host’s house hanging on the hills. Ms. Wagain Fu the elder daughter of headman was seen angry in her eyes in the first hand and finally in a low voice blamed us that because of “your delay you have to have take your dishes cold”. But we had a nice dinner that night cooked by the host family. It was simple and delicious. In the menu, we had boiled leaves of wild plants with no oil and less spice; green chili paste; wild cucumber and vegetable; green salads and smashed dried fish.

Dr. Reza introduced us to the headman family and explained our interest of the trip. The headman was very friendly, and well-known to Dr. Khan. Photographs taken by Dr. Khan in hisa previous trip of the family members and the nature’s bounty of the area were given to them . All the members of the family in association with the invited community leaders were enjoyed seeing their localities colorful images specially the lovely birds. Ms. Wagain Fu offered all of us specially prepared beetle nuts as symbolic good night. After gossiping till mid-night with the headman and his family, we the guests occupied drawing room space which is a wide wooden floor with two doors and two windows. We were given all warm blankets by the family but we returned those with many thanks as because we were well equipped with winter clothes and sleeping bags. We made a nice sleeping row and line like the style of “Jatra performers” and blessed god for having such shelter in the remotest mountain’s of Bangladesh.

At night we heard the wild calls of Nightjar , Owls, croaking of tree frogs, Barking deer’s and loud tokkey of Takhkhak, the forest Gecko.

We got up at around 6 in the morning with the smell of Mizoram coffee of boiling in the earthen oven, fueled by locally collected firewood. Lady of the house offered us hot coffee with fried maize. Dr. Reza got up earlier than rest of us and made a round of morning bird watch walk and told us that Hill Myans’ are also having their breakfasts in the old banyan and fig trees with dawn Chorus s joined by Leafbird, sunbird, bulbuls, orioles, iora and barbets. He asked us to join them and photograph because morning sun shined for a while despite the foggy sky. All the team members were ready by 7 am and started moving to the Banyan tree under the guidance of Dr. Reza khan. When we were out of the hut we saw sparkling dews on the grass blades as we walked through the hill slopes. A pack of pariah dogs were barking and chasing us believing us as invaders into their territory. The dogs here are dwarf and jet black which is totally different from the plain land ones. According to the locals these dogs are raised to be consumed as a matter of Mizo delicacy.

We followed Dr.Khan along a forest trail which enters into dense reserve. Dr. Khan with his lively demonstration explained us forest ecosystems, the linkage of wildlife with the plants. He was also helping us to identify the species of wildlife, even some of the insects.

We traversed the reserve by following the wildlife trails and encountered some rare and interesting wildlife. In a shallow water pool deep in the forest we found one of the smallest leaf turtle. This turtle is very cute and resemblance to a dead leaf. A group of uncommon dollar bird was seen in the upper canopy of Sajek forest. Avifauna of Sajek valley is very rich and we have recorded 140 species of birds during this expedition. Important sightings are: Rufous-throated Hill Partidge, Khalij Pheasant, Great Slaty Woodpecker, Great Pied Hornbill, Dollarbird, Bengal Coucal, Vernal Hanging Parrot, Forest Eagle Owl, Hogson’s frogmouth, Great Eared Nightjar, Imperial Pigeon, Steppe Eagle, Fairy Bluebird, Green Magpie, Himalayan Treepie, Greater Racket-tailed drongo, White-collared Blackbird, Large Nilvata, Sapphire Flycatcher, Spotted Forktail. Sajek is one of the last repository and reservoir of forest biological diversity. Forest biological diversity is a broad term that refers to all the life forms found within forested areas and the ecological roles they perform. As such, forest biological diversity encompasses not just trees but the multitude of plants, animals and micro-organisms that inhabit forest areas and their associated genetic diversity. Forest biological diversity can be considered at different levels, including the ecosystem, landscapes, species, populations and genetics. Complex interactions can occur within and amongst these levels. In biologically diverse forests, this complexity allows organisms to adapt to continually changing environmental conditions and to maintain ecosystem functions.

Forest biological diversity results from evolutionary processes over thousands and even millions of years which, in themselves, are driven by ecological forces such as climate, fire, competition and disturbance. Furthermore, the diversity of forest ecosystems (in both physical and biological features) results in high levels of adaptation, a feature of forest ecosystems which is an integral component of their biological diversity. Within specific forest ecosystems, the maintenance of ecological processes is dependent upon the maintenance of their biological diversity.

Recent developments for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) have the potential to provide benefits to local and indigenous communities. However, a number of conditions would need to be met for these co-benefits to be achieved. Indigenous peoples are unlikely to benefit from REDD where they have no secure land tenure; if there is no principle of free, prior and informed consent concerning the use of their lands and resources; and if their identities are not recognized or they have no space to participate in policy-making processes and/or lack the capacity to engage on an equal footing. There is a need for different types of capacity-building on indigenous issues and rights, both on the side of governments, as well as for indigenous peoples and local communities. This should include education and awareness-raising, indigenous to indigenous transfer of knowledge, and capacity building.

Forests are essential for human survival and well-being. They harbor two thirds of all terrestrial animal and plant species. They provide us with food, oxygen, shelter, recreation, and spiritual sustenance, and they are the source for over 5,000 commercially-traded products, ranging from pharmaceuticals to timber and clothing. The biodiversity of forests—the variety of genes, species, and forest ecosystems—underpins these goods and services, and is the basis for long-term forest health and stability.

Forests are amongst the most biologically-rich terrestrial systems. Together, tropical, temperate and boreal forests offer diverse sets of habitats for plants, animals and micro-organisms, and harbour the vast majority of the world’s terrestrial species. In the past, timber production was regarded as the dominant function of forests. However, in recent years this perception has shifted to a more multi-functional and balanced view. Today, it is understood that forest biodiversity underpins a wide ranges of goods and services for human well-being. Ecologically intact forests store and purify drinking water, they can mitigate natural disasters such as droughts and floods, they help store carbon and regulate the climate, they provide food and produce rainfall, and they provide a vast array of goods for medicinal, cultural and spiritual purposes. The health of forests and the provision of these and further forest ecosystem services depend on the diversity between species, the genetic diversity within species, and the diversity of forest types. Forests are home to an estimated 60 million indigenous people, who are directly dependent on forest resources and the health of forest ecosystems for their livelihoods. The cultural and spiritual identity of indigenous peoples is often linked to intact primary forests with their rich biodiversity. There are approximately 400 million indigenous people across more than 70 countries, with a high percentage located in tropical areas. They depend on the forest to sustain their ways of life, including their cultures and spiritualities .

The Convention on Biological Diversity recognizes the importance of traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and Article 8(j) of the Convention aims to respect, preserve, and promote such traditional knowledge. The Convention also recognizes the interdependence of indigenous and local communities and biodiversity. Forest operations, as well as landscape-level planning, should take into account both the rights and traditional knowledge of indigenous and local communities. The main principle for achieving this is through the effective participation of indigenous peoples and local stakeholders in decision-making and governance processes, on the basis of free, prior and informed consent to any projects, plans or changes that affect their communities, traditional lifestyles, and environment. Many sacred places in nature are associated with indigenous cultures. Although indigenous compose only about 15% of the human population, estimates range from 200-600 million persons depending on definitions and sources, they occupy a much larger percentage of the land in the world, perhaps up to half. Indigenous societies commonly use a wide variety of natural resources for their survival, economy, medicines, rituals, and other purposes. Historical, cultural, and spiritual aspects of the ecology of indigenous societies are grounded in the biodiversity, ecosystems, and landforms in their habitat. Thus, indigenous are most important to consider in exploring the relationships between sacred places, biodiversity, and conservation.

Sacred places are a new frontier for interdisciplinary research on their own merits and for their relevance for biodiversity conservation. The religious or cultural designation of an area as sacred, especially those which are relatively natural, may either intentionally or coincidentally promote the conservation of its associated biodiversity. Such sacred places can complement national parks and other protected areas established by governments. Collaboration among religious, governmental, scientific, and/or conservation agencies may be desirable for the protection of sacred sites and landscapes.

CHT is the last stronghold of the biodiversity in Bangladesh. Sporadic field visits by some naturalist generates a little information which is more than inadequate to design a plan/program for managing the biota of CHT. A large group of wildlife is extinct from CHT and a long list of wildlife in cue of locally extinction. This forest ecosystem provides a rich wildlife habitat. Among the mammals Elephant (Elephas maximus) is considered as the flagship species for these forests. Locally extinct wildlife is: Bengal Tiger, Rhinos, Peacock, Peafowl, White-winged Wood Duck, Leopard, Bear, Goat Antelope, Wild Buffalo, Hog deer, Swamp deer and Black-Eagle.

Chittagong hill districts are the last refuges of evergreen forest biodiversity in Bangladesh. These are Khagrachari, Rangamati, Bandarban and Cox’s Bazaar districts. Only 3 decades back the area was a contiguous forest cover and abode of flagship wildlife like tiger, elephant, Deer, leopard and Bear. Some areas were impenetrable and dense forest. Only few indigenous people were dwelling deep inside. Commercial tree plantations, illegal logging, dam megaprojects and forced displacement are responsible for the accelerated destruction of those precious ecosystems, which means the destruction of their biodiversity. Rubber, teak and eucalyptus monocultures for export have provoked negative ecological effects by the substitution of part of the forest, as well as conflicts between local communities belonging to the 13 ethnic groups that inhabit the region, and the Forest Department. Cultivation of tobacco in the productive hilly lands is another cause of forest destruction. Unluckily these types of situations are frequent throughout Asia.. The dam, constructed in 1964 which submerged 250 square kilometres of agricultural lands and forests belonging to the hill people, mainly the Chakma, and provoked the forced relocation of about 100,000 persons, who lost their homes and livelihoods. The displaced people were forced to clear new forest areas in order to carry out their subsistence agricultural practices.

The hill forests are abundant with numerous plant as well as animal species; an estimated 2,259 species of angiosperm were reported from Chittagong region alone. The top canopy of these forest ranges from 30 to 50 m in height and usually comprises various species of Garjan (Dipterocarpus sp.), Chapalish (Artocarpus chaplasha), Civit (Swintonia floribunda), Telsur (Hopea odorata), Buddah Narikel (Pterygota alata) etc. The second storey ranges between 15 and 25 m in height and the tree species are Jam (Syzygium sp.), Rata (Amoora wallichi), Tali (Palaquium polyanthrum), Kamdeb (Callophyllum polyanthum), Uriam (Mangifera sylvatica), Jarul (Legarstromia speciosa), Nageshwar (Mesua ferrea), Raktan (Lophopetalum wightianum), Gamar (Gmelina arborea) etc. The third storey ranges from 1 to 15 m and comprises saplings of species of upper two canopies as well as Vitex glabrata, Saraca indica, Mollotus philippensis, Macaranga sp., Castanopsis indica, Cordia myxa etc. Moreover there are bamboos, canes, climbers and fern also grow as undergrowth.in these forests.

Apparently Sajek and its neighborhood are parts of privately managed forest system on which government forest department has very little to do. So, all commercially viable trees have been felled by the local ethnic groups who own the land and the forest as has been done by the forest department in the government reserves. As these people are still great hunters and get almost all their protein needs from the animals they have wiped out all larger mammals and birds but smaller animals are flourishing. Only difference between the government and ethnic people is that the locals did not remove the whole forest minus the soil as has been done by the forest department. As a result, the non commercial forest species of plants have survived the onslaught on timber trees. This has given rise to a unique biodiversity that is found nowhere else in the country.

Sajek is still a heaven for birds. Beauty surrounding Sajek Valley in winter is simply unparallel that must merit visits by ecotourists. Forestry can have a variety of negative impacts on biodiversity, particularly when carried out without management standards designed to protect natural assets. The biodiversity in many parts of the hill range is still unexplored to determine their full potential, though preliminary surveys have given promising results. Therefore, conservation efforts with detailed biodiversity study must become a part of comprehensive plan to ensure the viability of these irreplaceable resources. If we fail to achieve the much needed co-ordinated approach we may find ourselves at the point of no return! Let us share the planet Earth with other species too!!

Article : Dr. Anisuzzaman Khan, Ecologist, Images by Mr. Asaduzzaman Khan

e-News® Xclusive