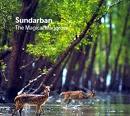

World’s largest mangrove forest

If there is no mangrove forests, then the sea will have no meaning. It is like having a tree without roots, for the mangroves are the roots of the sea.” – a fisherman on the coast of the Andaman Sea .

If there is no mangrove forests, then the sea will have no meaning. It is like having a tree without roots, for the mangroves are the roots of the sea.” – a fisherman on the coast of the Andaman Sea .

The Sundarbans is the largest contiguous block of mangrove forest remaining in the present day world. Along the mouth of the Bay of Bengal, it extends over 10,000 square kilometres in Bangladesh and India . Some 60 percent of the forest lies in Bangladesh and the rest in the Indian state of West Bengal . Said to be named after its maiden Sundari tree species, the Sundarbans is a globally significant ecosystem rich in bio-diversity providing habitat for around 334 plant and 453 animal species, including the world famous Royal Bengal Tiger. Several critically endangered species like rare sharks also find refuge in this forest containing Sundari, Gewa, Goran, Keora, Passur, Baen and many other trees and plants.

Besides its ecological value, more than four million people who live around the Sundarbans derive part of their subsistence extracting resources including fisheries, fuelwood, and non-wood forest products like honey. Livelihood of million others also indirectly depends upon this rich forest.

Every year a good number of tidal surges hit Bangladesh ‘s south and southwestern coastline and the Sundarbans bears the brunt acting as a vital barrier against all such calamitous lashings of the nature to protect the country’s southwestern coastlines including the regional towns and cities like Mongla and Khulna .

Every year a good number of tidal surges hit Bangladesh ‘s south and southwestern coastline and the Sundarbans bears the brunt acting as a vital barrier against all such calamitous lashings of the nature to protect the country’s southwestern coastlines including the regional towns and cities like Mongla and Khulna .

What is mangrove forest

“One perceives a forest of jagged, gnarled trees protruding from the surface of the sea, roots anchored in deep, black, foul-smelling mud, verdant crowns arching toward a blazing sun…Here is where the land and sea intertwine, where the line dividing the ocean and continent blurs, in this setting the marine biologist and the forest ecologist both must work at the extreme reaches of their disciplines.” That was how the Scientific American, a US specialised journal, described the mangrove forest in its March 1996 issue.

Growing in the inter-tidal areas and estuary mouths between land and sea, mangroves, able to tolerate saline water, provide critical habitat for a diverse marine and terrestrial flora and fauna. Healthy mangrove forests are key to a healthy marine ecology.

World’s largest mangrove forest

The main feature of the Sundarbans, which is likely to mesmerize a lone tourist, is its unique silence. Without doubt, one’s first impression of the dense forest will be its great silence. Forest creatures are very shy, but as the visitor picks his way along the trail or the water bodies around, which occupy one third of the Sundarbans Reserve Forest (SRF), he will realise how alive it is. Numerous living organisms are discreetly watching and waiting whilst one passes through their protective home. From time to time, the complete tranquillity will be shattered by a darting forest bird or a group of noisy monkeys jumping through the trees, disturbing the secretive residents and setting up a chain reaction when the ever-wary forest comes to a colourful and boisterous life for a moment, until silence reigns again.

Mangroves across the world are not particularly diverse in terms of their floristic composition, especially compared with rainforest ecosystems. While up to 75 species are recognised as genuine mangrove plants, the floristic composition of the Sundarbans is made up of 60 plus species. According to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) no other mangrove ecological niche in the world offers such a variety of associate mangrove vegetation as the Sundarbans does.

Mangroves across the world are not particularly diverse in terms of their floristic composition, especially compared with rainforest ecosystems. While up to 75 species are recognised as genuine mangrove plants, the floristic composition of the Sundarbans is made up of 60 plus species. According to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) no other mangrove ecological niche in the world offers such a variety of associate mangrove vegetation as the Sundarbans does.

Despite large scale indiscriminate felling of trees due to management problems, the natural regeneration process has kept the SRF alive and growing all the time. While all other forests in the world are being more and more technically managed and their soil productivity, regeneration of plants, reproduction of wildlife are controlled and monitored regularly as they are tending to lose their erstwhile individual characteristics, the SRF is continuing to evolve new and newer bio-geo-chemical cycles. However, it is also clear that the well-defined boundaries of rivers and canals and perhaps the presence of widely feared what the locals traditionally refer to as “maternal uncle” (the Royal Bengal Tiger) have added significantly to protecting the forest.

Ecology of the Sundarbans

The Sundarbans soil is characterized as moderately to slightly saline zone in the east and highly saline zone in the west. Its ecosystem is characterised by a very dynamic environment due to the effect of tide, flooding, salinity and even the cyclones. The fragile and intricate mangrove ecosystem depends on many variable components like tides, salt contents in water and soil, duration of sunlight, contents of sediment and organic matter in water, temperature and density of seawater and fresh water. The composition of terrestrial and marine flora and fauna also plays an important role in the mangrove ecosystem. If sun is regarded as the source of all energy flow, water must be considered as the nursing mother of an ecosystem.

World’s largest mangrove forest under threat

Mangrove forests are one of the most productive and bio-diverse wetlands on earth. Yet, these unique coastal tropical forests are among the most threatened habitats in the world as experts’ fear they may disappear more quickly than inland tropical rainforests because of lack of public notice. The Sundarbans too is no exception.

Mangrove forests are one of the most productive and bio-diverse wetlands on earth. Yet, these unique coastal tropical forests are among the most threatened habitats in the world as experts’ fear they may disappear more quickly than inland tropical rainforests because of lack of public notice. The Sundarbans too is no exception.

Most experts agree that due to direct and indirect impact of human interventions, far-reaching changes are taking place slowly but steadily — affecting the delicate Sundarbans ecosystem.

Much of such changes are not clearly visible. Direct human impacts are further worsened by the less- readily detected but perhaps more menacing impacts which threaten the mangrove ecosystem. Massive changes in both the adjacent agricultural lands and upstream areas with construction of polders, embankments or barrages are feared to have been generating fundamental changes in the hydrological regime of the Sundarbans.

The changes in freshwater flushing are visibly caused by gradual eastward shift of the flow of the Ganges River . The change is acknowledged as being historical in nature although the more recent impact of the Farakka Barrage in India and subsequent siltation in the Gorai is accelerating the process. It is believed that the changes affecting the salinity, flood intensity and periodicity, erosion, siltation and sedimentations may all be factors for perplexing and worrisome loss to the world’s largest mangrove system.

A number of species like Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), swamp deer (Cervus duvauceli), gaur (Bos gaurus), hog deer (Axis porcinus) and marsh crocodile (Crocodilus palustris) became extinct during the last 100 years from the Sundarbans.

The Royal Bengal Tiger is an inseparable part of the legend attached to the Sundarbans. The tidal mangrove forest is a rare habitat for this tiger species. But today they have been pushed due to habitat shrinkage. The SRF tiger population estimate in the past 20 years remained in the range of 350 to 400, the largest discrete population of the species in a single tract of natural habitat in the world.

The Royal Bengal Tiger is an inseparable part of the legend attached to the Sundarbans. The tidal mangrove forest is a rare habitat for this tiger species. But today they have been pushed due to habitat shrinkage. The SRF tiger population estimate in the past 20 years remained in the range of 350 to 400, the largest discrete population of the species in a single tract of natural habitat in the world.

But the preservation of the Royal Bengal Tigers is, by far, the most important challenge for those concerned for the protection of Sundarbans bio-diversity.

Incidental mortality due to diseases, illegal hunting and subtle changes in the Sundarbans ecosystem poses a serious risk for the survival of the Royal Bengal Tiger. Apart from that, the interaction with humans in the area, particularly the killing of humans by tiger, complicates the management of the area. IUCN has listed it as an endangered species in its Red Book.

The marsh crocodiles, once abundant, are already extirpated. The salt-water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) still survives in low densities and like the marsh crocodiles its population is being reduced through indiscriminate hunting and trapping for skins, quite apart from the immediate conflict with men. Despite an apparent reduction in illegal trade in its skin, the population shows little sign of recovery.

The marsh crocodiles, once abundant, are already extirpated. The salt-water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) still survives in low densities and like the marsh crocodiles its population is being reduced through indiscriminate hunting and trapping for skins, quite apart from the immediate conflict with men. Despite an apparent reduction in illegal trade in its skin, the population shows little sign of recovery.

Some 30 species of snakes have been recorded in the SRF and there appears to have been a general decline in densities or at least in their sighting particularly in the past two decades. The Rock Python (Python molurus) is one of the valuable SRF snake species, which is said to have declined over recent years. IUCN has listed it as a “vulnerable species.”

The results of four independent inventories undertaken over the past seventy years indicate that the overall volume of wood per hectare has decreased. Moreover, closer analysis of three inventories undertaken in 1959, 1983 and 1996 indicate a marked reduction in total standing volume for the two principal species of economic importance, Sundari and Gewa.

According to studies carried out at different times by the forest department, British ODA and UNDP/FAO sponsored Forest Resource Management Plan, the mean volume per hectare of the Sundari tree was 34.5 in 1959. The volume was reduced to 19.9 in 1983 and 17.8 in 1996. In case of Gewa, the mean volume per hectare was 8.7 in 1959, which was reduced to 4.6 in 1983, and 2.1 in 1996. The dramatic decrease is blamed on their over exploitation, legally and illegally, because of their commercial value and subtle changes in the ecosystem. A number of issues related to the Sundari, Gewa and Goran trees have emerged for immediate concerns of the foresters.

According to experts, the reasons for the decline in Sundari (Heriteria fomes) are twofold. First, as a valuable timber species with real commercial value, it has been subject to heavy exploitation. Second, increasing salinity as a subsequent impact of the subtle ecological changes, noticeable increase in salinity and siltation have resulted in hostile anaerobic conditions in which the Sundari finds it difficult for healthy respiration. This has resulted in die back whereby the tree is progressively defoliated from the top downwards. The phenomenon, in fact an infectious disease, is called “top dying.” The infectious top-dying disease of Sundari causes another management problem as experts said poor execution of infected trees invalidates the basic rationale for the “sanitation/salvage” method to save the uninfected trees. Long delays between marking and cutting causes more trees in an area affected by top dying eventually exposing them to “axes instead of saws.”

According to experts, the reasons for the decline in Sundari (Heriteria fomes) are twofold. First, as a valuable timber species with real commercial value, it has been subject to heavy exploitation. Second, increasing salinity as a subsequent impact of the subtle ecological changes, noticeable increase in salinity and siltation have resulted in hostile anaerobic conditions in which the Sundari finds it difficult for healthy respiration. This has resulted in die back whereby the tree is progressively defoliated from the top downwards. The phenomenon, in fact an infectious disease, is called “top dying.” The infectious top-dying disease of Sundari causes another management problem as experts said poor execution of infected trees invalidates the basic rationale for the “sanitation/salvage” method to save the uninfected trees. Long delays between marking and cutting causes more trees in an area affected by top dying eventually exposing them to “axes instead of saws.”

With regard to Gewa, forest officials say high pressure from deer populations in some areas of forest patches have caused nil regeneration of the species, leaving the areas under-stocked. The decline in Gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) is largely attributable to harvesting of around 50,000 m3 per annum as feedstock to Khulna Newsprint Mill for the production of newsprint over the years.

Experts say there is apparently little respect for the basic rule of leaving one stout stem to aid re-growth while cutting Goran trees, the second largest tree species of the SRF as all available merchantable stems are being cut from one area. However, acknowledging the importance of forest resources exploitation on a sustainable basis, the Forest Department imposed a logging moratorium in 1989 on all timber species except Gewa in the SRF.

Many factors contribute to mangrove forest loss, including the charcoal and timber industries, legal and illegal logging, oil spill, tourism industries, unplanned development projects, urban growth pressures, and mounting pollution problems. However, one of the most recent and significant causes of mangrove forest loss in the past decade has been the consumer demand for luxury shrimp, or “prawns”, and the corresponding expansion of destructive production methods of export-oriented industrial shrimp aquaculture along the forests.

Many factors contribute to mangrove forest loss, including the charcoal and timber industries, legal and illegal logging, oil spill, tourism industries, unplanned development projects, urban growth pressures, and mounting pollution problems. However, one of the most recent and significant causes of mangrove forest loss in the past decade has been the consumer demand for luxury shrimp, or “prawns”, and the corresponding expansion of destructive production methods of export-oriented industrial shrimp aquaculture along the forests.

No discussion of the ecology of the SRF would be complete without noting the problem of water pollution. Pollution from various sources is a major determinant of water quality — both in riverine and coastal areas of the Sundarbans. As approximately one third of the nearly 600,000 hectares of the Sundarbans area consists of tidal channels, and most of the reminder is subject to periodic inundation, impacts of water pollution are potentially very widespread.

The main threat today may come from outside the area in the form of pollution. On the northern edge of the area, Mongla , Bangladesh ‘ second seaport, is situated. This port and its associated marine traffic is a frequent source of oil spills and there is a permanent risk of accidents with chemicals. Moreover, toxic products (pesticides, etc.) and urban wastes enter the system due to upstream pollution in the huge Ganges catchment. Pollution may not be a direct source of mortality, but it may also reduce the health of the forests, increasing the mortality rate of the flora and fauna on the long term. Many products such as pesticides have also been proved to reduce the reproductively (birth rate) in animal populations.

Almost all Khulna-based industries like the match factories, fish processing plants, jute mills, steel mills, the Khulna Shipyard and newspaper mills discharge liquid or solid wastes directly into the Bhairab-Rupsha river system.

A very densely populated area surrounds the SRF. Around 1.2 million local users reside seasonally in the area for fishing and other resource use activities. Commercial hunting was a problem mainly before the 1970s and this resulted particularly in a serious depletion of the crocodile populations and to a lesser extent to the deer population. Although wildlife protection has improved significantly in the last decades, illegal hunting is still occurring on an incidental basis and fishery is having an adverse impact on the remaining turtle and crocodile populations as these animals are frequently caught up in fishing nets.

Due to natural processes the role of the Sundarbans to discharge the water of the Ganges and Brahmaputra catchment is decreasing as main waterways are shifting eastwards. As a result, the salinity of the Sundarbans is increasing — particularly in the western region. Further, the total annual discharge is decreasing due to intensifying land use (dams, irrigation) upstream. The role of this change is not yet clear, but is evident that it will influence wildlife populations and vegetation in the long term.

The expanding shrimp farming in the greater Khulna region has caused wide concerns for the rich bio-diversity of the Sundarbans. Experts say indiscriminate shrimp and salt cultivation already destroyed the valuable mangrove forest in Chokoria Sundarbans and fear that the ecosystem of the SRF too would be in jeopardy for the same reason in the near future. The fisheries department reckons that some 200 billion different fish fries are destroyed every year in course of gathering two billion shrimp fries from the water bodies along the Sundarbans due to the crude methods adopted for the purpose. Observers believe that the environmental and social losses would eventually eclipse profits from the shrimp sector.

Forest department officials admit that though slowly far-reaching changes are taking place pervasively in the Sundarbans. These arise from direct and indirect impacts of human influence in the area causing widespread quantitative and qualitative degradation of the resource base throughout the Sundarbans eco-system. According to forest inventory, it is clear that the level of illicit takeoff, some purely illegal and some quasi-sanctioned, may be quite larger than what could be scientifically justified for sustainable management of the SRF.

Consequence of mangrove deforestation

In many areas of the world, mangrove deforestation is contributing to fisheries declines, degradation of clean water supplies, salinization of coastal soils, erosion, and land subsidence, as well as the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In fact, mangrove forests fix more carbon dioxide per unit area than phytoplankton in tropical oceans.

With regard to the Sundarbans, experts have sounded caution that destruction of the forest will not only affect the ecology but cause far reaching impacts on national economy and causing immense damage to the marine resources of the Bay of Bengal, still economically unexplored and unexploited by Bangladesh. The loss of the Sundarbans would also expose the entire southwestern region of the country to frequent cyclones and tidal surges.

Mangrove forests once covered three-fourths of the coastlines of tropical and sub-tropical countries. Today, less than 50 percent of that is surviving. And then again, of this remaining mangrove forests, over 50 percent has been degraded and not in good form. Greater protection measures should be taken for maintaining high quality mangrove forests like the Sundarbans — a World Heritage Site.

e-News Exclusive