e-News® | The NEWS Company…NYC, Oct 21, 2015 : At an unmanned-systems industry conference in the mid-2000s, Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson talked of how his project to create an autopilot from Lego Mindstorm components could turn any model airplane into an unmanned aircraft, and he highlighted privacy and security issues that such accessibility could create.

Anderson is now co-founder and CEO of 3D Robotics, a leading manufacturer of consumer “drones”—small, inexpensive and easy-to-operate unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)—soaring sales of which are stoking fears over airspace safety, personal privacy and national security.

The result, barely a decade after Anderson foresaw the issues the coming drone revolution could create, is a rapidly evolving market for counter-UAS capabilities. And, as the development of radar spawned the discipline of electronic warfare (EW) and the cycle of countermeasure versus counter-countermeasure, developers of counter-UAS systems suspect they are at the beginning of a long battle. It could be argued the first generation of anti-drone countermeasures is like an irate individual protecting his privacy with a 12-gauge shotgun. But that point-defense option will not help government agencies and commercial entities protect the airspace around airports, major events, military bases and critical infrastructure such as nuclear power plants.

What is needed is a suite of capabilities to detect, track, characterize, identify, target and defeat unmanned aircraft, where defeat ranges from interfering with navigation or communications, through taking control of the air vehicle, to destroying it or targeting its operator. And that’s where it gets interesting. Backyard spying is still the public’s main concern about UAS, but for government agencies and public utilities the threat is more lethal than embarrassing videos. After 15 years of combating improvised explosive devices (IED) on waysides in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. and others believe they face an imminent threat back home from “airborne IEDs.”

A visible sign of this concern is the emergence of counter-UAS solutions, some with ties back to counter-IED systems deployed operationally. There have also been large-scale trials, in the U.K. and elsewhere, to assess the effectiveness of these systems against likely threats—including consumer drones such as the popular DJI Phantom that can be used for illicit surveillance, or worse.

The list of available systems grows longer and includes the Anti-UAS Defense System from a trio of small U.K. companies, Lockheed Martin’s Icarus, Selex ES’s Falcon Shield, Battelle’s rifle-like DroneDefender and the CACI International system to be evaluated by the FAA at U.S. airports (AW&ST-DTI edition, Oct. 12-25, p. DT17).

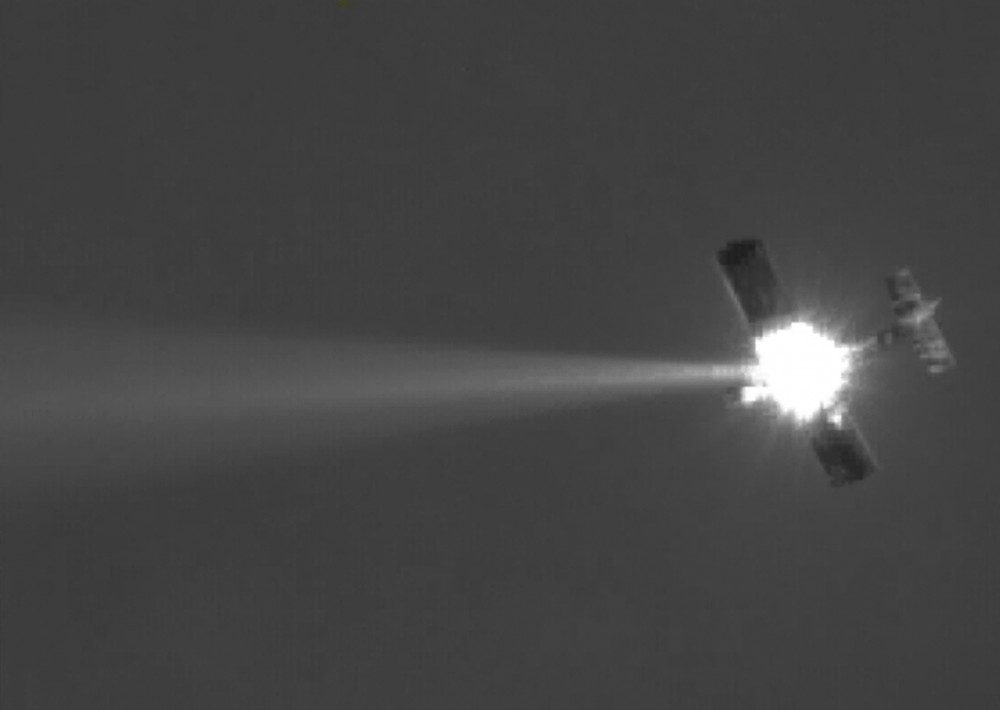

Typically a full system comprises a passive or active radio-frequency (RF) sensor to detect and track UAS, an imaging sensor to identify and target the air vehicle, and some form of RF inhibitor or jammer to disrupt or disable the UAS’s camera, navigation or communications, take control and pinpoint its operator. That is not as easy as it sounds, for two main reasons. One is unintended consequences. Disabling a UAS could make it crash, causing injury or damage and potentially dispersing dangerous substances. Jamming GPS would interfere with the navigation systems of nearby aircraft and can only be used briefly or must be targeted precisely.

“We cannot deny GPS near airports,” says Doug Booth, Lockheed Martin’s director of business development for cybersolutions. “There are other safe countermeasures we can use that are more specific and precisely focused on the vehicle.” Tellingly developed within Lockheed’s cyber business, Icarus has multispectral sensors, a signatures database and a non-kinetic payload that can deliver a “surgical strike . . . in seconds.”

Similarly, conventional EW “is a sledgehammer solution that disrupts the entire environment,” he says. “EW will knock a drone down, but turn it off and it is back in the air. Our technology allows us to seize control and land the vehicle. It is more cyber.”

The second reason is the question of who should own such systems. The sensing and jamming technologies come from the military and may not be transferable to the commercial sector to protect critical infrastructure or exportable to other nations with similar concerns about flying IEDs. For that reason, Booth says, the Icarus sensors are all passive—RF, acoustic and imaging—using technologies already exported. Active sensors are more problematic, but the countermeasures side is most sensitive and will depend on the customer. There is another reason companies are being coy about countermeasures—as with EW, they know illicit UAS users will develop counter-countermeasures, and the cycle will begin.